Menu

Menu

The University of Dallas’ Beatrice M. Haggerty Gallery is excited to celebrate the life, work and lasting influence of the late Heri Bert Bartscht, emeritus professor of art and founder of the university’s sculpture program in 1961, with the opening reception of Heri Bert Bartscht: 100 Years. The retrospective exhibition features a wide variety of Bartscht’s prized work through the decades, many of which are on loan from private collectors, including former colleagues, friends and members of the University of Dallas community, as well as a number of notable pieces from the university’s Permanent Art Collection.

A natural cultural leader, Bartscht quickly became a prominent figure in the Dallas art community, founding and directing the Dallas Society for Contemporary Art, the forerunner to the Dallas Museum of Contemporary Arts and the Dallas Museum of Art. In 1954, he received the top award in the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts’ annual art exhibition for his small bronze sculpture “Palm Sunday”; Bartscht continued to receive numerous awards and distinctions for his commissioned works through his decades-long career in professional sculpture and teaching.

The opening reception for Heri Bert Bartscht: 100 Years will take place on Friday, Jan. 31, from 6-8 p.m., and the exhibition will remain open for viewing through Saturday, Feb. 29, 2020.

Bartscht held an impressive command of a number of mediums such as stone, clay, bronze and metal (forged and welded), as well as a variety of woods, all of which he used to fashion his many works. On display are some of his best-known mythical and religious-themed creations such as “Charon,” “St. Francis” and “Moses,” showcasing his signature Romanesque style of figurative abstractionism. Also featured in the exhibit are “Portrait of Gus Gwin” and “My Mother,” demonstrating the sculptor’s mastery of proportional realism.

In June 1964, the Dallas Morning News reported on the famed German sculptor in a feature titled “Frozen Legs Give Sculptor License to Live and Create,” from inside Bartscht’s former Charles Dilbeck home in Dallas: “Heri Bert Bartscht’s splendid Spanish-style studio home on Canterbury Court overlooks a shady vista of Kessler Creek below. Lights on the patio play on sculptured figures of his ‘Annunciation’ and his powerful ceramic ‘St. Francis’ [included in the exhibit] … And there in the cool evening, the most accomplished sculptor to make Texas his home relaxed with his ever-present pipe. He talked of his art and the fates that brought him here. … ‘Why me?’ he said finally.”

On his 20th birthday, still working on his studies at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, Bartscht found himself drafted as a Nazi soldier in Hitler’s army: An “unenthusiastic telegrapher” forced into the destruction of Germany in the Nazi Blitzkrieg, he was also a fateful causualty of freezing Russian winter storms that resulted in his hospitilization and eventually captured by American troops, leading to his escape from the Nazis.

After the war, Bartscht returned to complete his studies at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, receiving the title of “Meisterschuler” (or Master Student), which included a private studio and 100 hours of paid model fees each semester. With gaining recognition for his work, he received (twice) Munich’s annual prize awarded to competing artists in the city. After meeting his wife, Waltraud (“Wally”), a fashion designer and late professor of German at the University of Dallas, the couple immigrated to America.

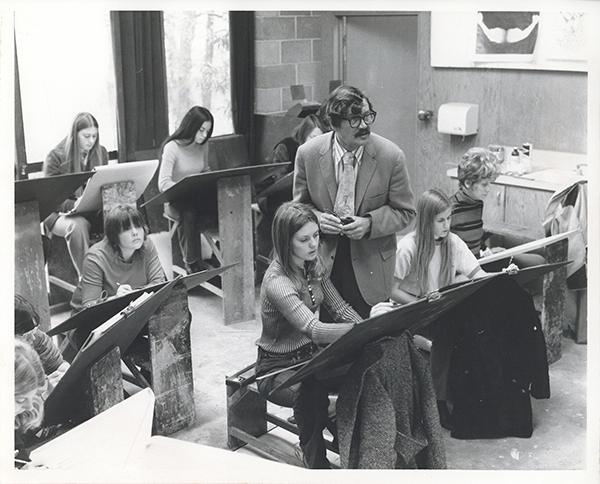

“A fateful trip to Texas in 1953 turned into permanent residence,” commented Bartscht in the forward to his book “Twenty Years of My Sculpture” more than a decade later. In 1961, the University of Dallas invited Bartscht to establish a sculpture program, which led to his nearly 30-year tenureship and much of the program’s success at the university. Bartscht’s papers, including personal letters and correspondence, two scrapbooks, and magazine articles, are available at the Smithsonian Institute’s Archives of the American Art research repository.

A devout Catholic, Bartscht included powerful religious text and themes from the Old and New Testaments in his work. His education in Bavarian art and craft, as well as his understanding of architecture and design, made him a popular choice for Methodist, Lutheran and Catholic churches across the region, including the university’s own Church of the Incarnation, designed by architects Jane and Duane Landry, that includes Bartschts’ 12 Stations of the Cross, a long-distinctive feature complementing the building’s interior.

“You can’t give a person talent … but if talent is there, discipline will free it,” noted Bartscht in an interview with D Magazine in 1977. “When I left the Academy, I knew how to carve, cast, weld, make mosaics and stained glass, work with practically any material. Now some parts of my training were overdone, such as learning how to use 90 different wood chisels, but in the end craft leads to the discovery of form and style.” The article continued, “There’s a medieval adage that a sculptor without an architect is like a child without a mother. Well, architects are discovering that it works the other way too. We’re collaborating now instead of trying to upstage one another.”

Bartscht gained a prominent and lasting reputation for liturgical art among peers, fellow artists, architects and private art collectors, nationally and internationally, and was involved in more than 50 commissioned liturgical works spread across the Southwest in various churches. More recently in 2014, the American Institute of Architects Dallas Chapter awarded the university's Church of the Incarnation the 2014 AIA Dallas Twenty-Five Year Award, the highest award bestowed annually by to an enduring post-war architectural work that is at least 25 years old.

In 2017, the editors and readers of D Home, a publication of D Magazine, also ranked Bartscht’s former North Oak Cliff residence No. 1 among the “10 Most Beautiful Homes in Dallas.”

“Heri Bartscht was the most influential individual in my early development as a maker of things,” said James Cinquemani, a former University of Dallas graduate art student and long-time apprentice of Bartscht, starting at age 17. “He taught me how to weld, braze and solder.”

His last year in high school, Cinquemani recalled taking some of his “homemade” sculptures to show his art teacher who, unbeknownst to Cinquemani, entered one of his wood carvings into the University of Dallas High School Art Competition. Receiving third in show and first in sculpture, Cinquemani remembered his introduction to Bartscht upon arriving for his award presentation. “We had a great visit. Turned out that I was his Dallas Times Herald paperboy many years before and lived only four blocks away from his home and studio. He asked if I could weld. I told him I could. He asked if I would be interested in spending the summer break at his studio welding on a crucifix for a big commission for a church in Brenham, Texas. Of course I was.”

Cinquemani added, “Though many people have encouraged and stimulated my creativity before and after, Heri has been and continues to be the most relevant factor in my own success in metalworking and life."

The Beatrice M. Haggerty Gallery is located in the Art History Building at the corner of Gorman Drive and Haggar Circle on the University of Dallas campus at 1845 E. Northgate Drive in Irving. The gallery, which is part of the university's Haggerty Art Village, is free and open weekdays 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday noon to 5 p.m. For more gallery information, visit udallas.edu/gallery or call 972-721-5087.

For more information (and high-resolution images) contact: Christina Hayes Haley, Gallery Manager, University of Dallas Beatrice M. Haggerty Gallery, 972-721-5087, gallery@udallas.edu.