As you know if you’ve read even some of our first UD Reads book, All the Light We Cannot See, it’s possible to build a radio from random, scavenged parts, as long as you can find the necessary random, scavenged parts, as Werner does in the book. This is also essentially what Assistant Professor and Department Chair of Physics Jacob Moldenhauer did as well, as he prepared for the “Across the Core” lecture he gave to faculty and staff just before the beginning of the spring semester: He scavenged parts from the Physics Department, and built a radio.

“I wanted the audience to see an example of the types of radios Werner repaired and used. I also wanted the audience to see the basic components of a radio and how simply it works,” said Moldenhauer. “In the spirit of how I like to teach physics, experiential learning, I wanted the audience to be able to touch and play with a radio to experience its parts. You can’t do that very easily with a radio in a box. I think this approach made understanding what Werner did very accessible to everyone in the audience. Plus, building a radio is something I always wanted to do, but never got around to it; this lecture motivated me.”

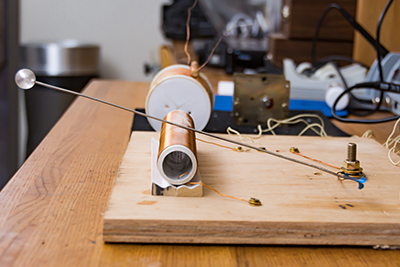

The radios Werner works on, and the one built by Moldenhauer, are primarily shortwave radios, with frequencies that fall between AM and FM. To build a radio like this, you need a few basic parts:

- An antenna, which is very important depending on the strength of the signal and the noise.

- A solenoid, or inductor, which is a coil of wire for inducing a magnetic field from an electromagnetic wave.

- A crystal earphone, which helps to amplify the signal with high impedance but isn’t necessary for strong signals. A crystal earphone’s real name is piezoelectric earphone, which means it’s made of a material that changes its shape when connected to a source of electricity; such materials include quartz, Rochelle's salt and some ceramics (like those made with barium titanate).

- A diode, or one-way gate for the electrons. A diode is a type of detector, or something that pulls the audio frequencies out of a radio wave, so we can hear them in our earphone(s). Detectors can be household items like baking soda, lead pencils, razor blades and rocks, but what Moldenhauer used for his radio is a germanium diode called a 1N34A, which you can buy, if you can’t come scavenge one in the Physics Department.

- Any upgrades, which include capacitors, vacuum tubes, transistors and batteries.

You then combine these materials to fill the holes in a crystal lattice structure (a diamond lattice). More specifically:

- Cut off the jack on the end of your earphone, if it has one, so that you have two long wires emerging from the earphone. If the wires are twisted together, that’s fine; they only need to be separate at the ends.

- Remove the covering (or insulation) from the ends of the wires to expose an inch of bare wire. You can either do this with your fingernail or with a wire stripper, which you can probably buy (or find) wherever you got the earphone or diode.

- Wrap one bare wire around one of the diode's wires, and tape it in place. You can solder the wires together, but you don’t have to.

- Attach half of the wire to one end of the diode. Attach the other half of the wire to the diode’s other end.

- Also attach one earphone wire to one side of the diode and the other earphone wire to the other side.

- Attach each end of the long wire to a tree to get it up in the air.

- Put the earphone in your ear, and listen to the radio.

“Building a crystal radio out of household items.” scitoys.com, scitoys.com/homemade_radio.html.

Menu

Menu