Menu

Menu

School never really clicked for Peter Searby, BA ’01, who grew up in Virginia on the edge of suburbia and the country. He loved riding bikes, playing sports, and immersing himself in nature and stories, but his overactive imagination felt stifled in the classroom. His family moved to Chicago for his high school years, and while his school was full of good people, he didn’t thrive. However, he discovered a love and a talent for guitar and began playing at 16. For two years after high school, he worked and honed his love for music, then visited his brother at UD and ultimately decided to come here.

“I saw that my brother had a great group of friends on a great journey of learning together,” said Searby. “UD gave me an expanded, grander vision of life. I was able to see how all elements of learning fit together to show how beautiful life and how crucial culture can be; culture is at the heart of transforming society. I realized this while I was at UD, but also afterward struggling to find my vocation both spiritually and professionally.”

After graduation, Searby took on several different teaching positions but always encountered the same difficulties with school that he had felt as a student himself. For example, at The Heights in Maryland, he found great camaraderie and the firm impression that a school’s culture is one of the most important things a school can give to its students, as well as the greater recognition of what it means to learn together, but he still disliked the pedagogy. Subsequently, as the director of middle school at Northridge (his Chicago alma mater), he perceived that boys needed something more in the realm of imagination, adventure and daring; they needed to get outdoors, out of their insulated surroundings.

“I never really found my place in the educational realm; I always had a sense that something was wrong — nothing resonated,” said Searby. “I came to see that there are certain systemic problems with the way boys are taught.”

While these ideas and realizations percolated, Searby always returned to music, playing in several bands spanning genres from Texas rock to blues. He has written a lot of music and made some albums; in fact, he was on the verge of doing just music, but what he had experienced at UD, that vision of something bigger, always nagged at him too. He realized again that there was a larger conception of culture and life, and that music could, and perhaps should, be just a part of this whole; he didn’t have to be a star, but instead could be a town musician and share his music, and therefore an element of culture, with the community in this way.

Further, Searby knew that somehow there was a way to combine these elements, learning and culture, to create a place where children — particularly boys — could grow in healthy, life-giving ways. He feels that modern schools — with a scarcity of opportunities for children to work with their hands and use their imaginations to explore their worlds — are doing boys in particular a disservice. Boys are so often pegged as having differences or disorders, as needing medications, when in fact many of their problems might simply stem from being in environments that are, one might say, biologically disrespectful.

From this recognized deficiency, Searby conceived the idea for Riverside Center for Imaginative Learning, of which he is both founder and creative director. In 2014, he launched Riverside.

“It started with a lot of prayer, leaving a secure job and taking a leap,” he said. “It was a lot of work just to get it off the ground; I thought at first that it could be the ultimate school for boys, like ‘scouts meets school’ — the great things a school can bring on adventure grounds in the country. However, we didn’t have donors or money, and as I started looking around and talking to families, I realized the idea resonated most with the homeschool community. They’re a bit more open to alternative education and out-of-the-box thinking when comes to how to educate. They saw this as a great opportunity for boys to meet and learn in a brotherhood, in a community, steeped in creative arts and outdoor adventure.”

Riverside, therefore, is not a full-time school but rather a supplemental educational center that offers “a landscape of adventure crafted specially for boys, but also providing co-ed programs, and cultural events for the whole family.” Riverside’s primary program is the “Tutorial,” the name taken from the tutorials that J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis would teach at Oxford. At Riverside, Tutorials center around the expression of story through creative media, using everything you can think of through which you could tell a story and adding in naturalist education and outdoor adventure. Their theater program is also very popular, with 40 to 50 children per play.

Currently, Riverside operates at two separate rented locations. One (22 acres in Big Rock, Illinois, complete with a forest, two ponds, a river, an old Civil War house, a woodworking shop and a machine shop) is under contract to purchase within the next year; there, they have been running camps, including two-week-long ranger camps. Hitchcock Design, a prestigious landscape architecture firm, just finished maps/drawings for a creative learning center at this location, which is an hour from Chicago with no traffic. The other location is a little closer to the city, on 80 acres with an old Tudor mansion.

Searby and his Riverside colleagues have written a substantial amount on pedagogy and also see Riverside as a place for educators to go to get ideas and creative curricula, as well as advice and training.

“We produce a lot of creative content,” said Searby. “Since we focus on the creative arts, imagination and story, we attract a lot of creative writers, people who would like being part of marketing or working for agencies.”

They have written five original musicals and become well-loved among the creative community. They plan to market these musicals to theater companies and schools, seeing Riverside as a hub for imaginative/creative learning and producing creative content, and as a home for adventurous educators who have a deep sense of mission rooted in the vision that life is an adventurous pilgrimage to heaven — and that education above all must serve that grand end goal.

Further, Riverside is currently looking for a tutor, if any UD alumnus has an interest in this opportunity. According to Searby, this person would be “part ranger, part elf, an outdoorsman but also a creative artist with an entrepreneurial spirit.” To apply, email petersearby@rside.org.

“Through all of my teaching jobs, I learned about caring for kids’ souls,” said Searby. “It’s very important to show you care for a deeper part of their being.”

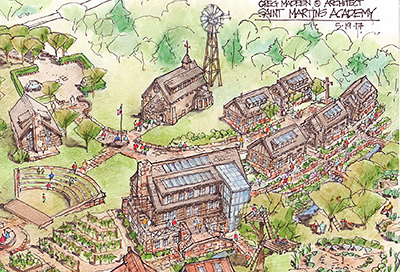

Also finding the education of boys to be a primary concern, Daniel Kerr, BA ’03, opened St. Martin’s Academy, a Catholic boys’ boarding high school in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 2018. St. Martin’s aims to nurture authentic masculinity, heal the imagination, awaken wonder and develop attentiveness; according to the school’s vision, “the fulfillment of our personalities can only occur through an ever-deepening relationship with Jesus Christ. And that relationship demands engagement from the whole person: body, mind and soul. In all that we do at St. Martin’s — farm-work, study and prayer — we seek to create a rich and fertile soil for God to do His work in cultivating Saints.”

Kerr is the youngest of six children and grew up in Fort Scott, “a small cow town” in southeastern Kansas. As his older siblings approached college, his parents began looking for an orthodox Catholic university that valued the humanities and the traditions that built Western civilization; UD fit this criteria perfectly. Kerr and all of his siblings came to UD, though he himself took an unusual route, stopping first at the University of Chicago and then Thomas Aquinas College in California.

“I ended up majoring in English, which you may not be able to readily tell given my proclivity for split infinitives and any number of forthcoming abuses of grammar,” said Kerr.

After graduating from UD, Kerr was immediately interested in helping found a boarding school and tried to get involved in a few start-ups.

“I had attended a boarding school in the latter years of high school, and it simply changed my life (all for the good), and my hope was to start a similar school in the Midwest that, perhaps uniquely, incorporated a serious work program on a sustainable farm,” he said.

For various reasons, none of these start-ups worked out, and Kerr realized that he needed more experience, credentials and resources in order to succeed in these types of projects. Enthusiasm and ideas he had in abundance, but these were accompanied by “very little practical sense and no real influence or even knack to make much happen.”

“My father used to refer to certain kinds of effective people as ‘can-do’ types,” added Kerr. “I was not a can-do type. I was more interested in thinking and discussing; doing seemed like a lot of effort. But I was also increasingly aware of this temperamental tendency, and so I remember very clearly asking God, if it was His will, to direct my life in such a way that some day I could make an impact in getting a school started. And he answered my prayers more powerfully than I could have imagined.”

In 2005, as Hurricane Katrina ripped apart the Gulf Coast, Kerr was tending bar in Fort Scott and, according to him, “going absolutely nowhere.” However, he had met a catastrophic claims adjuster, Adam Gardiner, a year previously, so he called Gardiner and asked if he could come down and just carry Gardiner’s ladder. Gardiner hired Kerr on the spot, and the two to this day remain business partners in AdjusterPro, a company they've built into a successful venture over the past 15 years.

“I owe a tremendous amount to Adam. Adam was and is the consummate ‘can-do’ type, an absolutely fearless doer, and he taught me everything I know about hard and soft business skills and ultimately, the art of turning a big idea into something real,” said Kerr. “Adam was a God-send, literally, and the experience and resources I have been able to deploy in starting St. Martin's Academy are simply God's generous answer to a prayer.”

In 2015, Kerr’s father, to whom he was extremely close, passed away, and this loss provided the impetus Kerr needed to finally found his school.

“He was a moral giant of a man and profoundly impacted hundreds and probably thousands of people's lives; he personally brought dozens of people to the faith,” said Kerr. “His passing put me at a kind of crossroads and gave my wife and me the occasion to reflect that life was short, and we'd better use our time well. That reflection showed how much Providence had been at work in our lives, and how the idea of the school, back-burnered for well over a decade, was clearly the vocation, the Opus Dei, we were meant to embrace.”

Kerr’s wife, Katie (Jones), BA ’07, pushed the decision through, and they have now completed a successful inaugural year at St. Martin's Academy.

The St. Martin’s approach to education was deeply influenced by John Senior’s The Restoration of Innocence, as well as the ideas and work of John Senior and his colleagues in the Integrated Humanities program at the University of Kansas.

“That means our pedagogy proceeds as much as possible in the poetic mode. Our focus then is on the primacy of the senses and the imagination, say as opposed to jumping straight to abstractions,” said Kerr. “I want our boys to have seen a proud rooster strut before his harem across the barnyard, or better yet get spurred from behind in a dastardly sneak attack, before reading about Chanticleer in Chaucer. I want them to see and taste what nitrogen, or a lack thereof, does to a tomato plant and its fruit, before going straight to the abstraction of the element itself. If wonder hasn’t been activated or if the imagination hasn’t been fired up, then whatever occurs by way of the transfer of facts, as Professor Grandgrind stresses in Dickens’ Hard Times, is only good for the temporary utility of passing a test or getting a grade.”

In terms of building a school for boys, while he could say a lot, Kerr has one big observation to emphasize: “In the early 1800s, 80% of households cited farming as their primary occupation. These were family farms, with young boys growing up working alongside Pa, Grandpa, their older brothers and Uncle Joe. Those households not farming were likely engaged in a craft: butcher, baker, candlestick-maker. Now, the family farm is gone, and less than 2% of households cite farming as their occupation. The craftsmen have been all but extinguished by Wal-Mart.”

For young men, not growing up working alongside male role models is highly problematic, says Kerr. This is because first, boys need the simultaneous physical exertion and creative expression that work affords; second, they need the proximate influence of their father (or Uncle Joe) to know how to persevere in the pursuit of an arduous good.

“Bishop Fulton Sheen once said that maturity comes principally through two things: pain and responsibility,” said Kerr. “At St. Martin’s, and in particular through our work program on the farm (e.g. milking cows, butchering chickens, slopping hogs, splitting wood), they get a good dose of both. The wonderful thing is, they crave it! Young men want to do hard things and build confidence and maturity in the process.”

Another significant component of St. Martin’s is that the boys are not on screens, whether smartphones, tablets or computers.

“Apart from the moral hazard of all-but guaranteeing a pervasive pornography problem, the widespread use of screens is lethal to the poetic mode of education described above,” explained Kerr.

Seventeen young men, split between ninth and 10th grade, completed this first year of St. Martin’s. Next year the school will welcome a new ninth grade class and add a few more students to the 10th and 11th grades, thereby reaching about 30 students. Each grade already has a waiting list for enrollment, so demand is extremely high. At capacity, the plan is to have 15 students per class for a total of 60. Currently students hail from 10 different states, coming from as far away as California and Georgia.

The school is situated on 200 acres on the Kerr Family Estate, which is divided among pasture, woodlands and a 25-acre watershed.

“It’s a real community that extends beyond the dormitories and classrooms,” said Kerr; he and Katie have six children and live on the premises. “Faculty members, their wives and children are frequently on campus and as a community, we are continuously celebrating feast days with good farm-raised food and homemade music. It’s great for the students to be around the kiddos and under the civilizing influence of the ladies.”

Kerr encourages his fellow UD alumni to explore the St. Martin’s website, and get involved however they might deem fit.

“I’d be delighted to address any questions or visit, so please reach out any time at dkerr@saintmartinsacademy.org or my cell at 620-224-8110,” he said. “My family and I are ‘all-in’ with our commitment to this project, and God has been so good in blessing St. Martin’s in our inaugural year. Our students are high-character kids from remarkably good families. We have a strong, cohesive vision and an unbelievably talented faculty whose every member has made real sacrifices in support of that vision. But we do need material support to bring it to full fruition. I would ask my fellow UD alums inspired by what we’re doing to consider supporting us at an especially critical time in the life of our school. Duc in altum!”