Menu

Menu

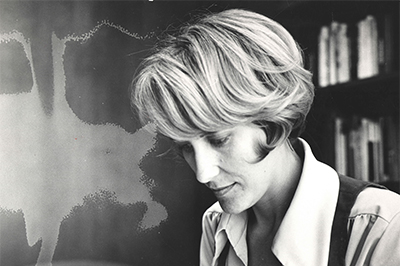

By Aspen Daniels Smith, BA '19

On a cloudless day during spring break, 18-year-old Eileen Gregory, BA ’68, was out exploring the newly paved Northgate Drive with a friend. The girls biked past fields dotted here and there with scrub oaks. Then they caught sight of a few speckled brick buildings. The place seemed deserted.

Curious, they rode across a field of parched grass and stickers that ruined their tires. A couple of guys were drinking coffee in the small cafeteria. Gregory can’t remember what they said, but it was a conversation that changed her life. There was something about these students — they were reflective, willing to jump into deep conversation. Gregory didn’t know any students like that at Irving High School, where she was a senior.

The students called Sybil Novinski, who was in charge of registration and recruitment. Novinski met Gregory in an office cluttered with boxes in Carpenter Hall.

“Within two minutes of speaking with Sybil, I knew that UD was my home,” Gregory said at a university event last year. “The students, and this remarkable woman who looked you in the eye and seemed really to see you — they belonged to a place that I had only dreamed about finding.”

Little did Gregory know that she would call UD home for decades, first as a student and later as the beloved “Dr. Gregory” to generations of future students.

She gave up her place at Texas Christian University to join UD’s Class of 1968, the university’s eighth freshman class.

They walked to class along dusty paths that turned to clayey goo when it rained and across wide-open spaces where the wind blew hard and trees hadn’t yet been planted. They found scorpions in showers and shoes. And the quality of their dinners declined steadily throughout the week, from meatloaf on Monday to fish sticks and Tater Tots on Friday.

“There was a simplicity and an austerity that we took for granted, exterior expectations pared down to essentials,” Gregory reminded her class at their 50th reunion. “[But for all that], there was a kind of imaginative excitement, a kind of merriness, improvisation, a take-it-as-it-comes, an all-hands-on-deck, an anything-is-possible attitude.”

Despite its newness, UD’s faculty was impressive. The Art Department was known in Dallas, highly educated Cistercian and Dominican monks were central to every department, and the intellectually ambitious Donald and Louise Cowan led the university. Gregory found herself immersed in an intense intellectual life: Her teachers held her to a high standard, and her classmates talked about ideas all the time. This intellectual atmosphere was exhilarating; Gregory and her classmates felt that they were receiving more than students at any other school.

In these early years, the university held Catholicism less as a conscious sense of identity even though there was a greater religious presence on campus.

“We understood that [Catholicism] was whole and large and welcoming, and that in that context there was nothing that you couldn’t talk about — so there wasn’t an emphasis on doctrine,” explained Gregory.

When Gregory started teaching in the ’70s, the university held a heroic ideal rather than the virtuous ideal it later adopted. One of the essay questions was, “What is a hero?”, which is a different question than, “What is a virtuous man?” The graduate program was highly influenced by James Hillman, an influential post-Jungian who came as graduate dean in 1978. Psychology was the strongest major, and faculty approached literature from a mythical perspective.

“The whole emphasis on imagination and heroic life is a little unruly and hard to perpetuate from one generation to another,” said Gregory.

This emphasis therefore later gave place to a more structured, philosophical approach.

Despite their serious academics, the students didn’t take themselves seriously. They had a tradition not just of playfulness but of downright irreverence. They parodied teachers during Charity Week, performed an “Immorality Play” on the mall (imitating the medieval morality play), and called the boys’ Augustine Hall the “North Hall Hornies.” An art major in a class above Gregory’s drew a mural in the Augustine lounge parodying the Sistine Chapel’s fresco, in which God was passing Adam a beercan and the other portraits were dorm occupants.

One of the wildest classes was the freshman class Gregory taught when she returned to UD in fall 1973. That year Lit Trad III (tragedy and comedy) was taught in the spring of freshman year. These freshmen entered into the plays and took them to heart.

“It was like throwing them into an abyss of some sort,” Gregory remembered. “They were too young to be hit with that as freshmen.”

On the Ides of March, an ancient Roman festival, a couple of the rabble raisers decided to throw a surprise party. They waited in a liquor store parking lot for an hour before it opened, and when Gregory walked into her classroom in Gorman Lecture Center at 9 a.m., she found a cart covered with a white cloth and strewn with flower petals set in the middle of the room. The students threw off the cloth to reveal bottles of champagne. The drinking age was still 18, and everyone had some. They were studying “The Bacchae” by Euripides, so struck by the inspiration of the moment, Gregory said, “Let’s do the play!”

The students jumped onto the round table with their books and chanted the chorale songs, swaying back and forth. Gregory played Dionysus, and one unlucky nerd volunteered to be Pentheus. He would begin every question in class with, “Pardon my ignorance … ” so his classmates called him “Pardon-My-Ignorance.” Just before the end of class, they got to the dismemberment scene. The class “dismembered” Pentheus by stealing his shoes and glasses, then took off with them. Gregory felt guilty and went all over campus with the student looking for his lost belongings until he found them.

The laws were more permissive, and everyone on campus drank more freely back then. Now Gregory wouldn’t allow that in her classes, she said.

“I like the playfulness; I like the improvisation,” said Gregory. “The drinking is not something you can romanticize; it’s just that it was just looser.”

At her class reunion, Gregory reminisced about those early years:

“We maybe didn’t know that we were pioneers, young people on new ground — but we were — blithely making fire in our sod huts, not knowing or caring that they were sod huts — beginners, out here on the edge of nowhere — and that was our good fortune,” she said. “That was a blessing.”